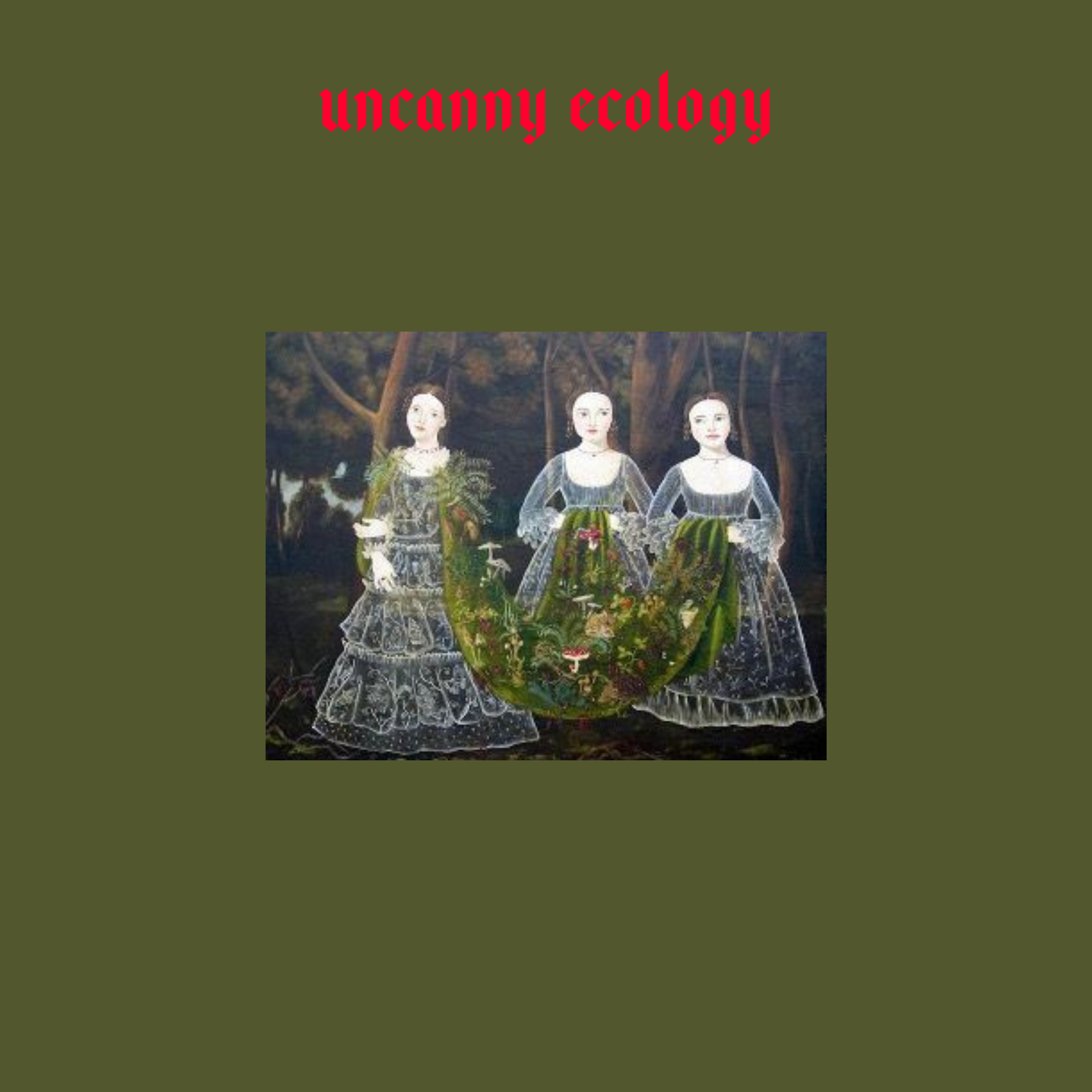

Uncanny Ecology

Fixed air: exile, un-home, paradoxes

What does the uncanny have to do with ecology? The first time I discovered this link was at a talk by the writer and scholar Rebecca Giggs, a chronicler of loss, a folklorist of disappearing biological forms, and a writer of beautiful stories.

During the talk, Giggs made the etymological link between the ecological and the uncanny.

The OED defines ecology as:

a branch of science dealing with the relationship of living things to their environments," coined in German by German zoologist Ernst Haeckel as “ologie”, from Greek oikos '“house, dwelling place, habitation" + -logia "study of.

The etymological root of ecology is the Greek ‘oikos’ meaning ‘home’.

The psychological (and literary critical) term ‘uncanny’ was popularized in Sigmund Freud’s essay of the same name.

The word ‘uncanny’ is derived from the German word ‘unheimlich’ meaning ‘un-homely’, but as Freud has argued, this term includes the word ‘home’ or ‘heimlich’ at its centre. The paradox is one of a home that is not a home.

To live in a world of climate disruption, hyper-capitalism, and unrest is to live in a place both familiar and unfamiliar, of safety and dread. It is to live in an un-home.

Rebecca Giggs in her essay ‘Whale Fall’ describes the uncanny experience of watching a beached whale live and die in front of her. She talks about the human interaction with the whale first to try to rescue the animal and then later to try to lessen its suffering when its inevitable death came to pass. She talks about an anxiety around this interaction, this unnatural order of things. She asks the question:

But what if we were now taking the wildness out of the whale? If deep inside whales the indelible imprint of humans could be found, could we go on recounting the myth of their remarkable otherness, their strange, wondrous and vast animalian world?

And later:

I put one hand briefly on the skin of the whale and felt its distant heartbeat, an electrical throbbing like a refrigerator. Life on that scale – mammalian life on that scale – so unfamiliar and familiar simultaneously. Oh, the alien whale.

The whale itself becomes an uncanny ecological figure in this essay.

Ra Page, in his introduction to a collection of short stories, The New Uncanny, says that:

The home is not just the setting and the target of the threat. The uncanny is somehow of the home, or under it. It squats in the very word Freud used for ‘uncanny’ in German, ‘unheimlich’, meaning literally ‘un-homely’. It lies beneath the house, under the heavy architecture of habit and belief, buried. And for a reason.

These live burials return in uncanny ecological stories. Amitav Ghosh describes fiction that deals with climate change as:

Almost by definition not of the kind that is not taken seriously. To introduce such happenings into a novel is in fact to court eviction from the mansion in which serious fiction has long been in residence; it is to risk banishment to the humbler dwellings that surround the manor house – those generic out-houses that were once known by names such as the gothic, the romance or the melodrama, and have now come to be called fantasy, horror and science fiction.

To write the ecological uncanny, then, is to spend time in these ‘generic out-houses’, and to lie squat beneath the heavy architecture of habit and belief.

Like the alien whale, the ecological uncanny is at once familiar and unfamiliar. It is feeling a distant heartbeat, and knowing it is not so different to our own. It is a home. It is un-home.